WASHINGTON (AP) — Michigan Sen. Debbie Stabenow was sitting in Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld’s conference room at the Pentagon, listening to him make the case that Saddam Hussein was hiding weapons of mass destruction.

At some point in the presentation — one of many lawmaker briefings by President George W. Bush’s administration ahead of the October 2002 votes to authorize force in Iraq — military leaders showed an image of trucks in the country that they believed could be carrying weapons materials. But the case sounded thin, and Stabenow, then just a freshman senator, noticed the date on the photo was months old.

“There was not enough information to persuade me that they in fact had any connection with what happened on Sept. 11, or that there was justification to attack,” Stabenow said in a recent interview, referring to the 2001 attacks that were one part of the Bush administration’s underlying argument for the Iraq invasion. “I have a son and a daughter — would I vote to send them to war based on this evidence? In the end the answer for me was no.”

As with many of her colleagues, Stabenow’s “nay” vote in the early morning hours of Oct. 11, 2002, didn’t come without political risk. The Bush administration and many of the Democrat’s swing-state constituents strongly believed that the United States should go to war in Iraq, and lawmakers knew that the House and Senate votes on whether to authorize force would be hugely consequential.

Indeed, the bipartisan votes in the House and Senate that month were a grave moment in American history that would reverberate for decades — the Bush administration’s central allegations of weapons programs eventually proved baseless, the Middle East was permanently altered and nearly 5,000 U.S. troops were killed in the war. Iraqi deaths are estimated in the hundreds of thousands.

Only now, 20 years after the Iraq invasion in March 2003, is Congress seriously considering walking it back, with a Senate vote expected this week to repeal the 2002 and 1991 authorizations of force against Iraq. Bipartisan supporters say the repeal is years overdue, with Saddam’s regime long gone and Iraq now a strategic partner of the United States.

For senators who cast votes two decades ago, it is a full-circle moment that prompts a mixture of sadness, regret and reflection. Many consider it the hardest vote they ever took.

The vote was “premised on the biggest lie ever told in American history,” said Democratic Sen. Ed Markey of Massachusetts, then a House member who voted in favor of the war authorization. Republican Sen. Chuck Grassley of Iowa said that “all of us that voted for it probably are slow to admit” that the weapons of mass destruction did not exist. But he defends the vote based on what they knew then. “There was reason to be fearful” of Saddam’s and what he could have done if he did have the weapons, Grassley said.

Republican Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina, then a House member who was running for the Senate, says the war will have been worth it if Iraq succeeds in becoming a democracy.

“What can you say 20 years later?” Graham said this past week, reflecting on his own vote in favor. “Intelligence was faulty.”

Another “yes” vote on the Senate floor that night was New York Sen. Chuck Schumer, now Senate majority leader. With the vote coming a year after Sept. 11 devastated his hometown, he says he believed then that the president deserved the benefit of the doubt.

“Of course, with the luxury of hindsight, it’s clear that the president bungled the war from start to finish and should not have ever been given that benefit,” Schumer said in a statement. “Now, with the war firmly behind us, we’re one step closer to putting the war powers back where they belong — in the hands of Congress.”

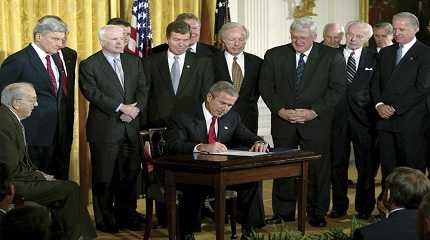

In 2002, the Bush administration worked aggressively, in briefing after briefing, to drum up support for invading Iraq by promoting what turned out to be false intelligence claims about Saddam’s weapons of mass destruction.

In the end, the vote was strongly bipartisan, with Senate Majority Leader Tom Daschle, D-S.D., House Democratic Leader Dick Gephardt, D-Mo., and others backing Bush’s request.

Joe Biden also voted in favor as a senator from Delaware, and is now supports repealing it as president.

Other senior Democrats urged opposition. The late Sen. Robert Byrd, D-W.V., urged his colleagues to visit the Vietnam Veterans Memorial on the National Mall, where “nearly every day you will find someone at that wall weeping for a loved one, a father, a son, a brother, a friend, whose name is on that wall.”

Illinois Sen. Dick Durbin, now the No. 2 Democrat in the Senate, recalled on the Senate floor earlier this month his vote against the resolution after the threat of weapons of mass destruction “was beaten into our heads day after day.”

“I look back on it, as I am sure others do, as one of the most important votes that I ever cast,” Durbin said.

Sen. Patty Murray, D-Wash., who also voted against the resolution, said that at the time, “I remember thinking this is the most serious thing I can ever do.”

For many lawmakers, the political pressure was intense. Democratic Sen. Bob Menendez of New Jersey, then a House member and now the chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, says he was “excoriated” at home for his “no” vote, after the Sept. 11 attacks had killed so many from his state. He made the right decision, he says, but “it was fraught with political challenges.”

For those who voted for the invasion, the reflection can be more difficult.

Hillary Clinton, a Democratic senator from New York at the time, was forced to defend her vote as she ran for president twice, and eventually called it a mistake and her “greatest regret.”

Markey says that “I regret relying upon” Bush and his vice president, Dick Cheney, along with other administration officials.

“It was a mistake to rely upon the Bush administration for telling the truth,” Markey said in a brief interview last week.