By AW Siddiqui

On 6 September 2019, Indian moon lander named Vikram, containing a lunar rover Pragya in its belly, failed while trying to attempt a soft landing in the south polar region of the moon, when it was about 2.1km away from its surface.

All eyes in the control room remained glued on the massive computer display, where a green dot representing the Vikram lander hovered, motionless. Subsequently, the “communications from the lander to ground stations was lost” was announced by ISRO chief K Sivan.

Read more: ISRO may have lost lander, rover: Official http://www.ummnews.biz/node/17371

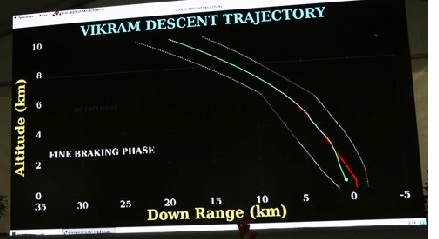

The mission was launched from the second launch pad at Satish Dhawan Space Centre on 22 July 2019 by a Geosynchronous Satellite Launch Vehicle Mark III (GSLV Mk III). The craft reached the Moon's orbit on 20 August 2019 and began orbital positioning manoeuvres for the landing of the Vikram lander, which was scheduled to land on the near side of the Moon, in the south polar region. However, at about 1:52 am IST, the lander deviated from its intended trajectory and lost communication. Initial reports suggesting a crash have been confirmed by ISRO chairman, and later, stating that the lander location had been found, adding "it must had been a hard landing".

Read more: Crashed landed Vikram located on Lunar surface: ISRO chief http://www.ummnews.biz/node/17440

According to The Verge, the Vikram lander was a critical part of India’s Chandrayaan-2 mission - a project aimed at learning more about the unexplored and highly intriguing south pole of the Moon. Numerous lunar spacecraft have gathered enough evidence about this region to suggest that significant amounts of water ice might be hiding on the south pole, likely in frigid craters that are in permanent shadow. India’s goal with Chandrayaan-2 was to land vehicles in this region to get a better understanding of the area’s composition and learn just how much water ice might be lurking there.

The primary objectives of Vikram was to demonstrate the ability to soft-land on the lunar surface and operate a robotic rover Pragyan on the surface. Scientific goals included studies of lunar topography, mineralogy, elemental abundance, the lunar exosphere, and signatures of hydroxyl and water ice, using a set of instruments, including a seismometer to measure lunar quakes and X-rays to help figure out the composition of the dirt (and potential water ice).

Watch: Meet Vikram — Chandrayaan 2’s Lander http://www.ummnews.biz/node/17471

The apparent crash is, in fact, the second time that India has sent a spacecraft hurtling into the Moon’s surface. The first time was deliberate in 2008, during India’s first mission to the Moon called Chandrayaan-1. The project sent an impactor probe on a crash course into the lunar dirt, to learn more about the material that got kicked up. For this follow-up mission, India hoped to keep the lunar lander and rover combo alive on the Moon for an extended period of time. The two bots were supposed to survive for the length of an entire lunar day — about two weeks, when the Moon is bathed in constant sunlight. The duo would have ceased operations when the lunar nighttime began, when the Moon is draped in darkness and surface temperatures plummet, sometimes below -200 degrees Fahrenheit (-130 degrees Celsius), reported The Verge.

But non of those possibilities materialized.

50 years after humans touched the surface of the moon, landing a probe on our next-door neighbor should be less difficult, perhaps even easy. The task once considered impossible should be something quite doable.

But it’s not. Why?

Though numerous lunar landings have happened since the 1960s, touching down on the Moon is still relatively difficult. It requires the precise firing of a vehicle’s rocket engine/s to lower it down safely on moon surface, which does not have an atmosphere like earth.

People working on lunar missions today should find it easier to achieve it because engineers and scientists are not starting their attempt from zero, as the United States and the former Soviet Union did. “In some ways it’s much easier,” says Yoav Landsman, an Israeli spacecraft engineer who worked on failed Beresheet lander, built by the Israeli nonprofit group SpaceIL. “But in the end, it’s not easy at all”, said Landsman to The Atlantic.

The only successful attempt this year was in January, when China landed a spacecraft, with rover included, on the far side of the moon, the face that never turns towards Earth.

According to The Atlantic, landing on the moon is certainly easier now than in the 1960s, for many reasons, some rather obvious, such as the strain of technological achievement in software and hardware that created supercomputers small enough to fit into pockets. During the space race, engineers had to figure out how orbital mechanics worked from scratch. And if an agency wanted something for its spacecraft, it probably had to invent the thing first.

Now many bits and pieces required to build a space craft come off the shelf, and buying them via internet is a lot easier when compared to Apollo era. Mission teams can shop online for sensors, computers, solar panels, propulsion systems, etc. without moving away from their desks. Even the rockets are available ready-made. “You can go out and buy a launch,” says John Thornton, the CEO of Astrobotic, an American company developing a lunar lander called Peregrine, and is paying the United Launch Alliance, a rocket manufacturer, to launch it in 2021, same way as the Beresheet, the Israeli lander, which was launched on a SpaceX rocket.

Today we know more about what the moon is like up close, thanks to orbiting spacecraft with high-resolution cameras that provide mission planners detailed photos that they need to carefully select landing sites. A small NASA mission, sent to lunar orbit in 2011, provided data about the gravitational forces around the moon that engineers now use.

But some mysteries persist. The lunar regolith, as fine as powder, is still poorly understood, said Alicia Dwyer Cianciolo, an aerospace engineer at NASA. “I don’t know if we got lucky on the other missions, but we feel like some of the new engine types and the thrust levels that we will have—we really don’t understand how it will stir up the different kinds of regolith in different locations on the moon”, Cianciolo told The Atlantic. Landers could kick up a cloud of dust that blocks sensors from detecting the craters or boulders that a last-minute engine burn might avoid. And the thrust could displace enough lunar matter that the spacecraft lands tilted, a position that could prevent a rover from rolling out safely.

The mysteries of the lunar environment make it difficult to predict, let alone perfect, the complicated maneuvers of a landing sequence. Simulations on Earth provide incomplete pictures of a preprogrammed process that unfolds autonomously millions of miles away. The spacecraft must go from a speed of thousands of miles an hour to nearly zero in about 15 minutes. It has to ignite its engines and thrust itself against the direction it is hurtling toward. As it slows, it falls, and more engine burns are needed to keep it from plummeting too fast, reported The Atlantic.

The spacecraft is equipped with sensors that track its altitude and scan the surroundings for any hazardous obstacles on the surface below. The inputs help the spacecraft make a snap decision right above the surface for any required manoeuvering, but the moon’s gravity, faint but influential, will eventually take over. If India’s intended attempt had worked, the Vikram would have manoeuvred for a gentle vertical landing.

Vikram failure “looks too familiar” to Landsman, who believes that a technical glitch doomed the lander, but Indian scientists may never know the details; the systems that could have answered their questions are probably scattered on the lunar surface.

The Vikram lander now joins the many other artifacts that humankind has delivered to the lunar surface, whether in one piece or many. Marina Koren wrote in The Atlantic.

Related news:

Softlanding of lunar probe 'Vikram' going as per plan http://www.ummnews.biz/node/17295

Indian landing module ready for touchdown on moon surface http://www.ummnews.biz/node/17045

Moon lander separation successful, says ISRO http://www.ummnews.biz/node/16999

References:

- India loses communication with lunar lander shortly before scheduled landing on the Moon, By Loren Grush, The Verge, https://www.theverge.com/2019/9/6/20853462/india-chandrayaan-2-lunar-landing-moon-vikram-crash-communication-failure

- India's Vikram Spacecraft Apparently Crash-Lands on Moon, by Jason Davis http://www.planetary.org/blogs/jason-davis/vikram-apparently-crash-lands.html

- Chandrayaan-2, Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chandrayaan-2

Note: Copying and republishing this content is allowed with the condition that it’s not changed (except spelling and/or grammatical mistakes), and the author and original source www.UMMnews.org is acknowledged.

*Opinions expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of UMMnews.